Sinking of H.M.S. Hood

|

.

The Admiralty announced

the loss of Hood at 9 P.M. on the 24th of May in the form of the

following simple communiqué:

"British naval forces intercepted early this morning off the coast of Greenland German naval forces including the battleship Bismarck."The enemy were attacked, and during the ensuing action H.M.S. Hood (Captain R. Kerr, C.B.E., R.N.) wearing the flag of Vice-Admiral L.F. Holland, C.B., received an unlucky hit in the magazine and blew up.

"The Bismarck has received damage and the pursuit of the enemy continues."

Adding in a final poignant

sentence:

"It is feared there will be few survivors from H.M.S. Hood."37

Thousands of British

sailors and citizens recalled receiving the news as the single greatest

shock of the war. Several officers recalled decoding the message

again and again, in the absolute certainty that an error must have been

made. The story hit the papers the next day. NAZI BATTLESHIP

BISMARCK SINKS THE HOOD IN NORTH ATLANTIC DUEL; BRITISH GIVE CHASE; RAF

FLIES TO CRETE, BLASTS 14 AIR TRANSPORTS read the verbose headline in the

New York Times for Sunday the 25th. Describing Hood as a symbol

of British naval power and the ". . . show ship of the British Navy," the

paper called the action the greatest naval victory of the war since the

River Plate. The Times of London carried the story matter-of-factly

on page 4 of the edition of Monday the 26th, calling it ". . . the heaviest

blow the navy has received in the war," and in an editorial entitled "The

Price of Sea Power" characterized it as a ". . . heavy calamity." German

communiqués, which were remarkable for their lack of self-congratulation,

stated simply that Hood had been sunk in a five minute engagement

between a German flotilla and heavy English naval forces, and that the

Germans had received no damage worthy of mention in return - a not unreasonable

assessment at the time.

It wasn't long before British recriminations began. A writer to the Times of London, in a letter entitled "DESIGN OF THE HOOD NO MISCALCULATION -The Handicap of Age" stated the Hood had not been destroyed by a "lucky hit" but because ". . . she had to fight a ship 22 years more modern than herself. This was not the fault of the British seamen. It was the direct responsibility of those who opposed the rebuilding of the British Battle Fleet until 1937, two years before the second great war started. It is fair to her gallant crew that this should be written."38 The Admiralty, still reeling from the shock of the loss, chose to file the letter as part of the official record.

It is clear that the Admiralty responded to the loss about as rapidly as circumstances allowed. In a letter to the Controller and the First Lord, Sir Dudley Pound wrote on 28th May:

"The loss of HOOD from internal explosion after a few minutes' action at 23,000 yards is disturbing, as we thought that the defects in construction which led to the similar loss of three capital ships at Jutland had been eliminated. . . . Now, after the lapse of 25 years, we have the first close action between one of our capital ships and that of the Germans since the Battle of Jutland and the HOOD has been destroyed in what appears to the onlooker to be in exactly the same manner as the QUEEN MARY, INDEFATIGABLE and INVINCIBLE, in spite of the action which was taken subsequent to Jutland to prevent further ships being destroyed as a result of 'flash'. . . . In the light of this experience, will you please have the whole matter re-opened, going back to the records of the last war and see whether any theory can be evolved that would explain the loss of all four ships from some cause other than 'flash'."39

Sir Dudley's letter set

in motion the activities of the first inquiry to investigate the causes

of the loss, convening on 30 May 1941 and headed by Vice Admiral Sir Geoffrey

Blake.40 The results of the board,

a two page report signed by S.V. Goodall, and classified "SECRET," were

made available to V.C.N.S. and First Sea Lord on 2 June, 1941, only nine

days after the loss and only a week after Prince of Wales returned

from Hvals Fjord.41 The report

began:

"This report contains the findings of the Court, but not the evidence on which these findings are based. Hence, some of the points raised in the following remarks may have been dealt with in the evidence and the Court's conclusions reached after full consideration of such points."

With some qualifiers,

the report found that ". . . a 15-in shell fired from 'Bismarck' at the

range and inclination of the fatal fifth salvo could, if lucky and if possessing

sufficient delay, reach the after magazines," noted that the explosion

seemed to originate at the base of the mainmast, and stated, "It is extremely

difficult to associate this observed fact with the explosion of the 4-in

magazines, the forward bulkhead of which group is 64 ft abaft the center

of the mainmast." Almost unbelievably, as an alternative, the board

felt that even a single torpedo head exploding in its confined box ". .

. would most probably break the ship's back and result in rapid foundering."

The report concluded:

"It is important the doubts concerning the loss of this ship should be cleared up if possible at a very early date, as although action is being taken to implement the lessons of both explanations, it is impossible to do this quickly for all our old capital ships if the true explanation is found by the Court. Moreover, it will never be possible to give these ships such protection to their magazines as to ensure certainty [sic] that modern shells and bombs under all circumstances that may exist in modern actions cannot reach their magazines."

Not surprisingly, when

one considers the speed with which it was prepared, the report was rather

incomplete. Although Goodall made this clear in the introduction,

it was nonetheless criticized quite severely by some of the recipients.

In a memo dated 18 July 1941, V.C.N.S. wrote:

"D.N.C. in his minute on this paper raises a point of great importance, i.e., as he points out the report contains the findings of the Court, but not the evidence on which those findings are based. . . . it unfortunately transpired that no shorthand notes of the evidence were taken."This matter of the blowing up of the HOOD is one of the first importance to the Navy. It will be discussed for years to come and important decisions as to the design of ships must rest on the conclusions that are arrived at. This being so, it seems to me that the most searching inquiry is necessary. . . . I regret to state that in my opinion the report as rendered by this Board does not give me confidence that such a searching inquiry has been carried out; in particular the failure to record the evidence of the various witnesses of the event strikes me as quite extraordinary. . . . I also note that of the three survivors from the HOOD one only was interviewed. This strikes me as quite remarkable.

". . . I propose, therefore, that a further Board of Inquiry should be assembled as soon as possible and that the necessary witnesses should be made available. At this enquiry every individual in every ship present who saw the HOOD at or about the time of the blowing up should be fully interrogated."42

To that end, a second

board of inquiry, headed by Rear Admiral H.T.C. Walker R.N., began hearings

in August of 1941, delivering its final report on 12 September. Not

surprisingly, the second report was much more thorough than was the first,

taking evidence from a total of 176 eyewitnesses to the disaster, including

71 from H.M.S. Prince of Wales, 89 from H.M.S. Norfolk, 14

from

H.M.S. Suffolk, and 2 from H.M.S. Hood, the third survivor,

Midshipman W.J. Dundas being ". . . not available to give evidence to us."43

In addition, evidence was taken from two officers who had recently served

aboard Hood, and from a number of other technical witnesses nominated

by the Director of Naval Construction, the Director of Naval Ordnance,

the Director of Torpedoes and Mining and the Chief Superintendent of the

Research Department. In summary, the general findings of the second

hoard of inquiry were as follows:

a) The signal for the final turn 20° to port was flying at the time of the blast, but never executed.b) The fire was started on the port side of the boat deck of Hood by the 3rd or 4th salvo from Bismarck. The preponderance of evidence suggested that it was a cordite fire from U.P.44 and possibly 4-in ammunition in the vicinity. The fire on the boat deck had nothing to do with the final explosion.

c) Evidence as to the seat of the explosion was divided between before and abaft the mainmast with a bias towards the former. The large explosion, which was visibly similar to magazine explosions aboard World War I battlecruisers, was due to the explosion of the after magazines.

d) A large majority of witnesses heard little or no noise of the explosion.

e) Very few witnesses could be very definite about the debris from the explosion, and 'a large number of small pieces' best described the general impression.

f) The ship sank in three minutes or less.

g) Evidence generally indicated that the salvos from Bismarck in the order they fell could be described as: 1) ahead, 2) astern, 3) straddle with hit, 4) close short, 5) probable hit. One salvo of 8-in H.E. was also noted astern of Hood.

h) The explosion or detonation of torpedo warheads was of low probability, and at any rate could not have been the cause of the loss.

i) If the muzzle velocity of Bismarck's guns was between 830 and 930 meters per second then a 380mm penetration to the main magazines was "quite possible"; if over about 930 meters per second, then the probability was "considerable." [The actual initial velocity of Bismarck's guns was c. 820 mps.]

j) An effective underwater hit was relatively unlikely due to the c. 75 foot [23 meter] fuze delay required to reach the magazines.

The nineteen page report

concluded:

"(1) That the sinking of the HOOD was due to a hit from BISMARCK's 15-in shell in or adjacent to HOOD's 4-in or 15-in magazines, causing them all to explode and wreck the after part of the ship. The probability is that the 4-in magazines exploded first.(2) There is no conclusive evidence that one or two torpedo warheads detonated or exploded simultaneously with the magazines, or at any other time, but the possibility cannot be entirely excluded. We consider that if they had done so their effect would not have been so disastrous as to cause the immediate destruction of the ship, and on the whole we are of the opinion that they did not.

(3) That the fire which was seen on HOOD's boat deck, and in which U.P. and/or 4-in ammunition was certainly involved, was not the cause of her loss."45

Any discussion on the loss

of the Hood must make it clear at the outset that there are important

inconsistencies as to the range and target angle of Hood at the

time she was hit. Published statements of the range, for example,

range from an apparent low of 14,500 yards [13,260 meters], given in Raven

and Roberts, to an apparent high of 19,685 yards [18,000 meters] given

in Müllenheim-Rechberg.46

Although in more elementary treatments some of this is no doubt due to

confused reading of accounts by writers making no distinction between "gun

range," i.e. the range set on the sights of the guns to obtain a hit, and

"navigational range," the geometric distance between the firing ship and

the target, discrepancies in more knowledgeable presentations are difficult

to explain. Even official track charts have proven inconsistent and

unreliable. The track chart shown below, which was developed with

the aid of a computer, has been redrawn from information taken from a large

number of British and German sources and is, so far as I know, the first

to reconcile all of these outstanding discrepancies. Geometric reconstruction

of the various accounts indicates that the most probable range at impact

was in the vicinity of 18,100 meters. Given this information, accurate

figures for the appropriate terminal conditions of Bismarck's shells

can be inferred from contemporary German range tables.

There are also major difficulties

in determining Hood's exact target angle at the time of the blast.

Some descriptions of the action suggest that Hood was either in

the midst of completing her turn of 20 degrees away or that she had in

fact completed it when the fatal explosion occurred.47

Witnesses in Prince of Wales, including Captain Leach and Cdr. Rowell,

were consistent however in affirming that although a 2 blue was flying,

it had yet to be executed when Hood blew up. The boards of

inquiry specifically found that the final turn was never executed.

The turn would have only taken about twenty seconds to complete, however,

and there is at least circumstantial evidence that Hood might indeed

have at least begun to turn when she exploded. Numerous witnesses

confirmed that Prince of Wales had to alter course to starboard

to avoid wreckage of Hood as she steamed past. It is very unlikely

that such a maneuver would have been required unless Prince of Wales

had already commenced a turn of 2 blue herself. Assuming that Hood

and Prince of Wales maintained the normal practice of turning together

and recalling that Hood was flag and thus controlled the movements

of both British ships, it is clearly unlikely that Prince of Wales

would have begun the turn without receiving an 'execute' signal from Hood.

In my own opinion, the most probable explanation is that Hood had

just begun the final turn, perhaps without yet sending the execute signal

to

Prince of Wales, and that Prince of Wales began the turn

by reflex, in effect completing Hood's intention at the exact moment

she exploded. In fact, both of Hood's surviving witnesses

who gave detailed testimony stated that a turn to port had just begun when

the explosion occurred. In describing the final seconds of Hood,

Able Seaman Tilburn stated ". . . we started turning round to port and

we were hit somewhere, and the whole ship shook and a lot of debris and

bodies started falling all over the deck." Briggs confirmed this, stating

". . . it was either just immediately after or whilst we were doing this

turn to port that the explosion took place." When asked if the execute

signal had been made before the explosion, Briggs replied "I am not certain

but I think it had."48

Able Seaman Robert Tilburn, R.N., one of three survivors of Hood's action with Bismarck and Prinz Eugen. He was lying down adjacent to Hood's forward funnel when the ship disintegrated around him. HU 50191. |

|

Range Table for 38cm SK C/3451 Projectile Weight 800 kg Initial Velocity = 820 mps |

||||

|

(meters) |

(deg.) |

(sec) |

(mps) |

(meters) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

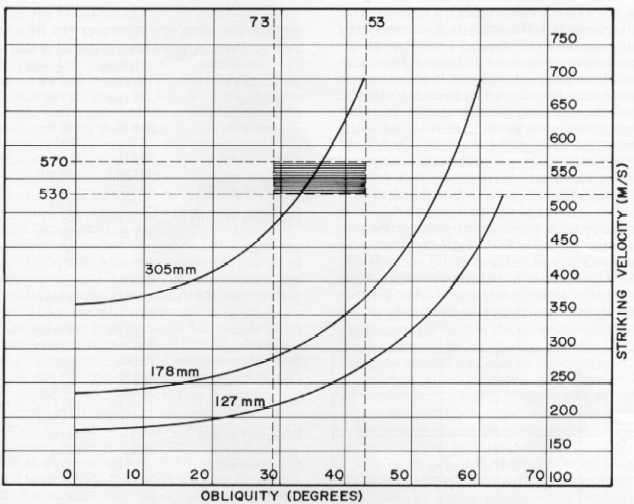

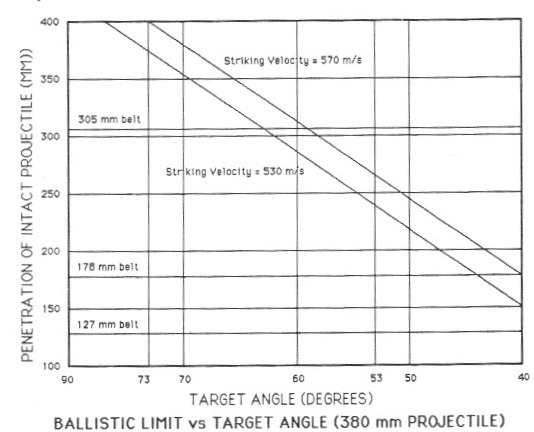

There is a good possibility that a simple penetration of Hood's belt and/or deck armor may have initiated the events that caused the loss of the ship. The arrangement of the armor dictated that even if Hood had been engaged directly from abeam, the minimum obliquity of impact would have been c. 24°, equal to the 14° angle of fall plus the 10° slope of the armor. An analysis of the track charts of the action indicates that at the fatal moment, assuming she had not begun the final turn, Hood's target angle would have been approximately 53°.52 For this angle, corresponding to a shot approaching from 37° forward of the beam, the resolved obliquity would have been approximately 43.85°.53 German armor penetration curves, redrawn below,54 indicate that at the predicted striking velocity of 530 meters per second, the penetration for an intact projectile into face-hardened armor would have been approximately 240mm. An intact penetration of the 305mm main belt would therefore have been improbable, although either of the thinner sections would have been easily perforated. Calculations yield an exit velocity of about 450 meters per second from the 127mm plate and 365 meters per second from the 178mm plate.55 The impact would have certainly decapped the projectile and forced it to exit closer to the normal than its impact angle, meaning that the projectile might well have been traveling nearly horizontal and nearly athwartships, as it left the plate.

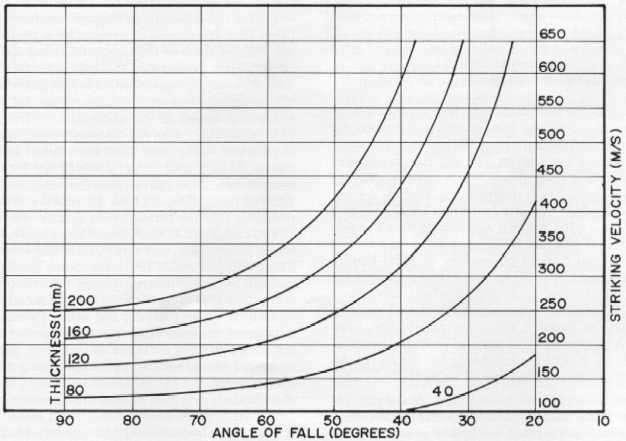

Depending upon the exact

location of the hit, a shot perforating the 127mm belt would still have

to penetrate approximately 160-180mm of deck armor in order to reach the

magazines. If the hit went through the 178mm belt instead, only about

130mm of deck penetration would have been required, but in compensation

the shell would have been traveling much more slowly. In either case

the trajectory of the projectile, its velocity, and its high obliquity

would have rendered useful penetration to the area of the magazines highly

unlikely.56 Even assuming the

projectile were not rejected or deflected by Hood's deck armor,

the fuze delay of the German projectiles would have probably detonated

the shell before it could reach a magazine. Assuming that the required

deck penetrations reduced the projectile's average velocity to half of

the plate exit velocity, a nominal fuze delay of 0.035 seconds corresponds

to a travel of only eight meters at best, not enough to reliably reach

a magazine.57 The German penetration

diagrams are reproduced below.

Armor penetration curves for the German 38cm projectile against face hardened armor. The shaded area indicates the probable limiting conditions at impact, with the figures "73" and "53" at the top referring to the probable target angles at the beginning and the end of the final turn and the figures "570" and "530" representing the probable range of striking velocities. |

Armor Penetration curves for the German 38cm projectile against homogenous (deck) armor. Note that at angles of fall less than about 20 degrees penetration of any sort was considered problematical. These curves were adapted from those given in "Unterlagen." |

The German penetration curves redrawn in another form. |

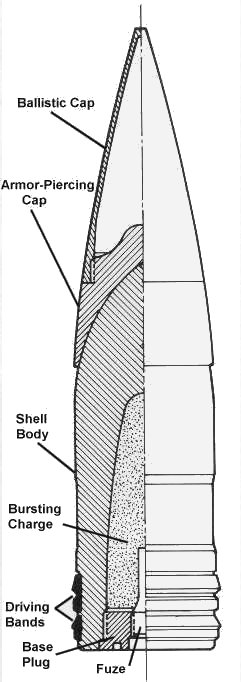

Cross-section of one of Bismarck's 38cm projectiles. Note the relatively flat front of the armor-piercing cap, which may have greatly enhanced its diving capabilities. Sketch by William Jurens with additional work by Tony DiGiulian |

38 Letter to the editor The Times, 28 May 1941, reproduced in ADM 116/4351 pp. 17.

40 The other members of the board were Capt. C.F. Gammel of H.M.S. President and Capt. C.H.J. Harcourt of H.M.S. Duke of York.

41 The entire first report is given in ADM 116/4351 pp. 6-7.

42 ADM 116/4351 pp. 10-11. The last three paragraphs of the memo have obviously been "patched on" from text prepared using a different typewriter.

43 ADM 116/4351 pp. 89 et. seq. It is worthy of note that Norfolk was fifteen miles distant at the time of the blast, and Suffolk was nearly twice as far, so the evidence of the witnesses from these ships is rather general in nature.

44 The abbreviation 'U.P.' stood for Unrotated Projectiles, i.e. rockets.

45 The entire final report is given in ADM 116/4351 pp. 89-108. As a matter of interest, the board also listed their estimates of 90° immunity zones for British ships against German 15-in shell. In rounded metric units, these were: KGV class 13,700 - 31,000 meters, Nelson class 13,700- 32,000 meters, Queen Elizabeth class 16,450 - 25,150 meters, Royal Sovereign class 16,450 - vulnerable (18,750 meters with 25mm deck armor addition). Renown's immune zone was negative, with the belt limit at 25,600 meters and the deck limit at 21,950. The immune zone is the area far enough away from the enemy to prevent penetration of the belt armor, yet close enough in to prevent plunging fire from penetrating the deck.

46 Other values are 16,500 yards [15,087 meters] quoted in both Roberts and Bradford, and 21,130 yards [19,300 meters] scaled from a track chart in Grenfell. Whitley [German Cruisers of World War II, U.S. Naval Institute, 1985] gives the ranges from Prinz Eugen to Prince of Wales as 24,500 meters at 0553 and 16,000-17,000 meters at 0559. Dulin and Garzke [Battleships - Axis and Neutral Battleships of World War II, U.S. Naval Institute, 1985] give the range from Bismarck as decreasing to 18,300 meters after the fatal shells had been fired, which implies the range was higher before that time. A track chart in Schmalenbach yields a range of c. 18,000 meters at the time of the blast. The official British track chart gives the range as 16,300 yards, i.e., 14,900 meters.

47 E.g. Bradford pp. 184 and Kennedy pp. 86. Statements that Hood's 'A' arcs were closed up until that time were false. Drawings of the ship show that Hood's after turrets could train and fire within 30° of the bow, although her starboard turret rangefinder optics would have been 'wooded' by the after superstructure until an angle of 43° had passed. Official drawings of Prince of Wales show her after turrets could have engaged up to 45° from either bow. As Bismarck was bearing approximately 53° off the bow during the final run in, it is evident that both Hood's and Prince of Wales' 'A' arcs had in fact been well clear since the turn at 0555, provided one would have been willing to accept some damage from muzzle blast. Captain Leach's statements that Y turret would not bear probably mean that 'Y' turret would not bear comfortably.

48 ADM 116/4351 pp. 360-365. Perhaps significantly, however, Briggs was equally positive that the turn was one of 40° instead of the 20° it actually was.

49 These values have been converted and rounded to metric units, in Imperial units the thicknesses were 5-in, 7-in, and 12-in., respectively.

50 As an aside, in the process of reviewing preliminary drafts of this manuscript, several readers took me to task for using "bullets" as a synonym for "shells" or "projectiles." Although I have thus deleted this noun from the paper, readers should note that it is not entirely unknown. For one example, see S.E. Morison, History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, Vol. XII. pp. 190 et. seq., "The proportion of 8-inch bullets in the heavy cruisers was 66 per cent."

51 All range tables in this paper are derived from "Unterlagen" described in the bibliography.

52 Strictly speaking the target angle is defined as the angle between the firing ship's bow and the line of sight to the target, an angle which is used to develop the lead angle used in surface gunfire. In the absence of a better term, I have used it here to describe the angle from which the projectiles from Bismarck actually arrived on the Hood. Hood and Bismarck would not have moved significantly with respect to each other during the approximately 28 second time of flight of Bismarck's projectiles.

53 The equations to determine the resolved obliquity for a sloped armor plate are basic but are rarely reproduced. In simple terms Oo = Arcos [Cos(Fd)Cos(Id)Cos(Bpd - Rd)Sin(Fd) Sin(Id)], where Oo equals the resolved obliquity, Bpd equals the target angle, Id equals the inclination angle of the armor, Rd equals the rotation angle of the armor, basically its horizontal orientation within the ship, and Fd equals the angle of fall. Vide, Okun, Nathan "Frames of Reference," unpublished manuscript in the author's collection.

54 Vide "Unterlagen und Richlinien . . ."

55 As a first approximation, Yr = (V2 - VI2)0.5, where Yr equals the residual velocity, V equals the striking velocity and VI equals the limit velocity for the plate in question. These exit velocities were obtained directly from the German data, and thus do not exactly match the (more accurate) values given in Table II, and derived from more modern computations.

56 Note that all the figures for armor thicknesses given here ignore the roughly 38mm thick backing plates and teak cushion behind the face hardened armor, a not insubstantial barrier that would reduce the penetration of impacting projectiles even further. Thus the penetration values given here, are, if anything, somewhat optimistic.

57

When examining Hood's cross sections, an eight meter travel along

the line of flight corresponds to an athwartships distance of only about

6 meters. Assuming a target angle of 53°, and that the projectile

was undeflected by its passage through the armor, the ratio of actual travel

to projected travel when superimposed on the ship's cross section is equal

to cos 37°, or 0.7981. Of course, the projectile would have been

deflected athwartship during penetration, so this may be looked upon as

a minimum value. It is worth noting that the angle of fall would

have been greatly reduced at the same time, which would have tended to

keep the flight line above the crowns of the magazines.